This is the third and final part of my history of the invention of the bicycle. Here’s the link to Part 1 and the link to Part 2.

From the New York Times, August 22, 1867 …

So the improved velocipede, the one we see so frequently in the streets [of Paris] mounted by fashionably dressed young men, is a vehicle with pedals and a complication of cog-wheels with cumulative power … The experts in this new and cheap mode of locomotion, make twelve miles an hour, and a higher speed will be attained.”

Finally!

The pedal has arrived. The birth of the modern bicycle is upon us. There’s no turning back, and the bicycle would soon transform transportation, commerce, recreation, travel, women’s rights and sports all over the world.

The velocipede described in the Times story, upon which riders could go so fast “they are scarcely visible, and the man has the comical appearance of flying through the air on an imaginary tread-mill” was the creation of Pierre Michaux, a Paris blacksmith of whom many attribute the invention of the pedal-powered velocipede.

But, did he really? This statue says he did …

Nevertheless, there’s much debate and no definitive proof about whether it was Michaux or his employee, Pierre Lallement, who came up with the idea to add a pedal to the front wheel in the early 1860s. Lallement later moved to the United States, received a patent for his version of the pedal-powered bike and manufactured them, as did Michaux in France. Michaux’s son, Ernest, may have also played a role in the development of their machine. The exact details are lost to history, so let’s give all three some credit.

Then again …

And then there was Macmillan

Several years after the Michaux/Lallement creation, there came word from Scotland that – hold everything! – not one, but two of our own added pedals to the Drais creation, years before Michaux and/or Lallement.

But, once again, did they really?

Macmillan or Dalzell … or neither?

From the Aberdeen Weekly Journal and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland newspaper, July 5, 1893 …

The honor of this invention has long been credited to Gavin Dalzell, a cooper of Lesmahagow, but it now seems to be well established that Kirkpatrick Macmillan, of Courthill, Kerr, was the first to ride the improved machine which could be propelled by the rider with the feet off the ground – in other words, the crank-driven bicycle.

Neither the Macmillan or Dalzell models were actually “well established” beyond a shadow of a doubt, as this article declares, and there have been many doubters over the ensuing years who question whether either made a crank-driven bicycle. It’s possible, but there were no real-time newspapers articles to verify their existence, as there are for Blanchard, Sivrac and Drais. And Michaux/Lallement.

An article that ran in several newspapers in May 1896 tried to prove that the deceased Macmillan, a blacksmith, was the true inventor of the modern, crank-driven bike in 1840, citing letters from men who claimed they saw Macmillan’s vehicle in action years before. A letter written by Thomas Wright and quoted in the story states that he knew Macmillan well, “we were nearest neighbors and many a ride I enjoyed on his ‘dandy horse’ when I was about 12 years of age. He made the first foot driving dandy horse about 1840.”

The same article cites a letter written by William Brown of Jarrow on Tyne, who writes that his parents knew Macmillan and his machine and, “on one occasion when Macmillan rode his machine to chapel at Durisdeer the lads of the village and Mr. Brown’s father followed the cyclist for a considerable distance, and then Macmillan remained overnight at Mr. Brown’s house. On the following morning he indulged Mr. Brown’s mother by allowing her to ride his cycle before leaving on the return journey, and, as Mr. Brown says, she may therefore safely claim to be numbered among the very earliest lady cyclists.”

The way he referred to Mr. and Mrs. Brown is confusing, but I think they were his parents. They sure did write different back then (if you’re reading this in 2138, please feel free to comment on my antiquated writing style).

This is from a Boston Globe, February 16, 1896, story tracing the history of the bicycle: “Shortly after the appearance of the McMillan machine another Scotsman produced a rear driving safety similar to McMillan’s, the difference being in the position of the treadles.” This was Dalzell, who had also passed away.

An 1842 newspaper story in a Glasgow paper talks of “a gentleman from Dumfries-shire bestride a velocipede of ingenious” design who hit a little girl and was fined five shillings. Some point to this as proof of Macmillan’s machine, while others say a blacksmith would never have been described as a “gentleman.” And, the doubters say, if this machine was so revolutionary, why didn’t it attract more attention? That’s a good point.

So, what do you think? Did Macmillan invent the modern crank driven-bicycle, and did Dalzell then make a few improvements? Did Michaux and/or Lallement invent the pedal-powered bicycle on their own – or adapt and improve what Macmillan and Dazell built? Any and all of this is possible, and it seems we’ll never know the truth, despite what this plaque says …

The bone crusher reigns supreme

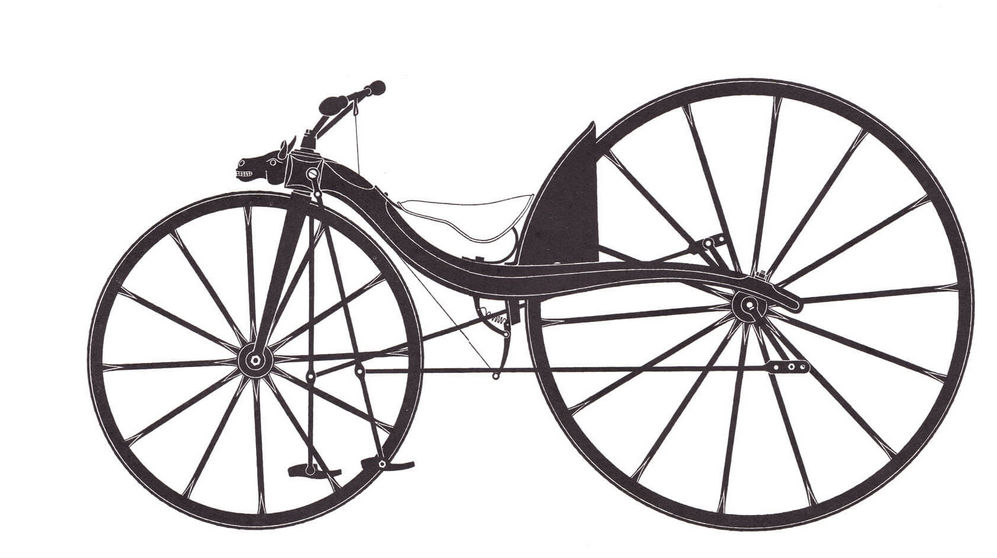

Called the bone crusher because of it’s rough ride (rubber tires were well off in the future), the bicycles created by Michaux and/or Lallement in the mid-1860s were a huge success. The year 1868 marked an explosion in the use of these new-fangled and fantastically fast machines.

For example, from The Brooklyn Union, January 14, 1868 …

“A party of one hundred people, each mounted on a velocipede, lately left Paris all together for Versailles.”

From The Morning Post, London, July 14, 1868 …

“A novel race was run last week between a horse and a car and a velocipede. M. Carrere in a one-horse car [carriage], and M. Carcanade in a velocipede, started from Castres [France] at twelve, and the victory to be decided in the favour of the person who first arrived in Toulouse. The race was a very keen one, M. Carrere having arrived in Toulouse at six and M. Carcanade at 6:25.”

What’s it like to ride a bone crusher? Here you go…

Races between velocipedes and horses were quite common, as the velocipede was pitched as a replacement for the horse: cheaper, faster, easier to store. And it ate less. These races continued for decades, including one rather amazing one between two cowboys from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and two champion cyclists. I’m still researching this story. Stay tuned.

From the New York Tribune, November 21, 1868 …

“It is the rage of Paris, and at country chateaux throughout the Empire hosts and guests indulge in velocipede races, instead of watching their horses run under the whip … Velocipedes are used by French sportsmen and by French artists; and at several Parisian theaters they play a prominent part in the more striking scenes on the stage. They are driven by messengers, peddlers, clerks and school boys.”

From The New York Times, November 25, 1868 …

The paper reported “regular two-wheelers racing in Central Park … We presume that ‘velocipede clubs’ will now be formed, and velocipede contests waged; then of course will follow velocipede matches for the ‘Velocipede Championship of the United States,’ and then international matches for the ‘Championship of the World.’”

The bone crusher was popular for a while, and innovations and new ideas continued at a furious pace …

The next big thing – the ordinary

We have the Starley family of England to thank for a couple of huge improvements and the modern bicycle. The ordinary or penny farthing bike was created by James Starley, a British engineer, in 1871. It was hard to mount and dismount, with a huge front wheel and tiny back wheel, but was smoother and faster than the bone crusher and quickly caught on.

Here’s a video of several penny farthings in action …

And then: the safety bike

Another Brit, John Kemp Starley, (the first Starley’s nephew) came up with the “safety bicycle” in 1885. The “Rover” had two wheels equal of size, and pedals that turned the back wheel via a chain. The safety bike revolutionized cycling, the bike industry and changed the world in many ways. This basic design, and the diamond-shaped frame, is pretty much the way the modern bicycle is still designed … and a good place to end my history of the invention of the bicycle.

Thanks for reading … I had fun, I hope you did as well. Stay tuned for lots more fascinating bicycle history in the weeks to come. Sign up on this blog’s home page for email alerts.

I enjoyed your blog. I wrote my high school term paper on this subject back in the ’70’s, doing my research at the Cleveland Public Library. I got points taken off by calling the high-wheelers “ordinaries”. The teacher considered that an adjective. “Ordinary what”, she wrote.

LikeLike

I too was in high school in the 70s and remember doing research: you had to look in that giant book (year by year) that listed topics and where to find them in newspapers and magazines, then you had to hope your library had the microfiche! And then spooling it through…and printing pages, 10 cents a copy. It’s a little different now, perhaps better, but I do miss the old days. Hope you got an A!

LikeLike

I am a history buff and thoroughly enjoyed this post.

LikeLike

Thanks Geri, more to come!

LikeLiked by 1 person