“I can’t see,” shouted Charles Minthorn Murphy. A cloud of dust and cinders enveloped the cyclist as he pedaled furiously on plank-covered railroad tracks behind a specially equipped train car filled with railroad officials, timers and newspapermen.

It was June 30, 1899, and Murphy, one of the top bike racers of the early to mid 1890s, was determined to make cycling history and pedal at a speed that seemed impossible: 60 miles per hour for a measured mile. The Associated Press wrote “those who could get close enough to realize all that was going on gasp in amazement at the speed of the rider and tremble for his safety …”

***

The dream of riding a bicycle a mile in a minute first came to Murphy all the way back in 1886, when he was 15 or 16 years old, and just starting to race on his high-wheeled, penny farthing machine.

Or so he would claim years later.

It’s difficult to separate fact from exaggeration when it comes to the legend of Mile-A-Minute Murphy. He led an adventure-filled, well-publicized life and wasn’t shy about detailing and perhaps embellishing his many accomplishments when newspapermen gathered around in search of a story. Hardly a week went by, from the early-1890s until well into the 1900s, without a story about Murphy and his accomplishments as one of the fastest men on two wheels; his dream of pedaling a mile a minute; his design for a flying machine (a few years before the Wright Brothers and Kitty Hawk); daring deeds rescuing damsels in distress as a bicycle-riding, New York City policeman; and his exploits as one of the first policeman to ride a motorcycle and fly an airplane.

According to Murphy, he came up with his mile-a-minute scheme after riding the equivalent of the distance in one minute and 19 seconds on a home trainer (a stationary bicycle). “The track record, at that time [1886], for one mile was three minutes and nineteen seconds,” Murphy wrote years later. “I demonstrated that in the absence of the wind pressure, one could ride at least two minutes faster for a mile than the figure just mentioned. I declared that I could follow a railroad train … I immediately became the laughingstock of the world. The more people laughed, the more determined I became to accomplish the feat.”

It seems unlikely anyone would ask for or cared about Murphy’s opinion on cycling speed when he was 15 or 16. The first newspaper record of his quest would come nine years later.

“Charles Murphy, of Brooklyn, announces that he will try before June 1 to ride a bicycle a mile in one minute, and there is a heavy bet that he will [not] come within ten seconds of it,” reported The Baltimore Sunon January 25, 1895. “It is supposed he will have a track constructed between railroad tracks, as nothing but a locomotive could pace a wheelman in any such time.”

On the same day, The Buffalo Enquirer reported: “The very idea is enough to daze the ordinary mortal … If the rider has any insurance on his life it is odds on that the company cancels the policy without much ado.” A syndicated cycling column joked that: “The tramp and the mile a minute bicycle resemble each other insomuch that neither will work.” Perhaps this is where Murphy got the notion of people were laughing at his mile-a-minute goal.

Murphy was certain he could do it. “I figured that the fast-moving locomotive would expel the air to such an extent, that I could follow in the vacuum behind, which meant exactly the same as if I was riding on a ‘home-trainer’ or in dead air,” he said.

***

Murphy and his older brother, William, were members of Brooklyn’s Kings County Wheelmen. They began racing in 1886, with William getting the better of his younger brother the next few years until Charles emerged as the star of the family and one of the fastest men on the national circuit.

The introduction of the safety bicycle in the late 1880s, followed by the invention and widespread use of pneumatic tires, led to an explosion in cycling. Wheelmen and bloomer-wearing wheelwomen were everywhere in the 1890s. Cycling became a major sport in the United States and around the world. Amateur and professional races were held in hundreds of cities and towns at county fair on dirt tracks, on outdoor velodromes and on indoor, wooden-planked venues during the winter months.

“Charl has won in four years’ racing over 350 prizes,” wrote The Brooklyn Citizen on June 1, 1893, of Murphy. “He is 22 years of age, 5 feet 8 ½ inches tall and weighs 140 pounds.”

***

The possibility of riding a mile a minute may have come to Murphy in 1894. “Charles Murphy rode a mile on a home-trainer last night in 59 seconds,” the Brooklyn Citizen wrote on January 13, 1894. “His pedaling knocked the record out and the racing men silly who witnessed the feat. The best previous record was 1m. 3s., made by Bicyclist Culver.”

Murphy was in peak form that year, winning scores of races. He beat the great Walter Sanger in a mile race in Kansas City on August 22. A few weeks later, Sanger set a new record for the unpaced mile during a race in Springfield, Massachusetts: 2:07 1-5.

“Charles M. Murphy covered himself with glory by winning three important races, the two-mile scratch race, the mile indoor championship, and the five-mile scratch race [at Madison Square Garden],” the New York Times reported on November 30, 1894.

***

The next year (1885) got off to a rough start for Murphy.

“There was a trolley smash up this evening [in New York], and nearly a dozen persons were more or less severely injured,” newspapers reported on January 2, 1895. One of the injured passengers was Murphy. The New York Sun reported he “had continual hemorrhages and doubted if he would be able to ride a bicycle again. Last year he received over $20,000 in prizes [and] threatened to sue the railroad company.”

Murphy, who may have exaggerated the extent of his injuries, healed quickly. He soon began racing and winning and continued to talk about riding a mile a minute. “The mile open, the race of the day, went to Charles M. Murphy, who holds the present mile competition record of 2.01 4-5,” reported the Baltimore Sun on July 27, 1895. “In this contest, Murphy defeated a great field, including [Eddie] Bald and [Arthur] Gardiner.”

First prize was a $200 diamond.

Not only was Murphy going faster, so were America’s trains. A New York Central Railroad train traveled 436.5 miles in 407 minutes, an average speed of just over 64 miles per hour. “This beats the English record for fast running, which was 63 1-4 miles per hour,” reported the Daily Times of New Brunswick, New Jersey on September 16, 1895.

Now, all Murphy needed was a railroad company with a speedy train willing to back him. It would take a lot of logistical support to set up such an attempt.

In December 1895 the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported the “deal has been made whereby Murphy will make the trial on the Southern Pacific road in California some time next spring.”

The deal fell through.

***

Perhaps Murphy should have kept his idea to himself and out of the newspapers.

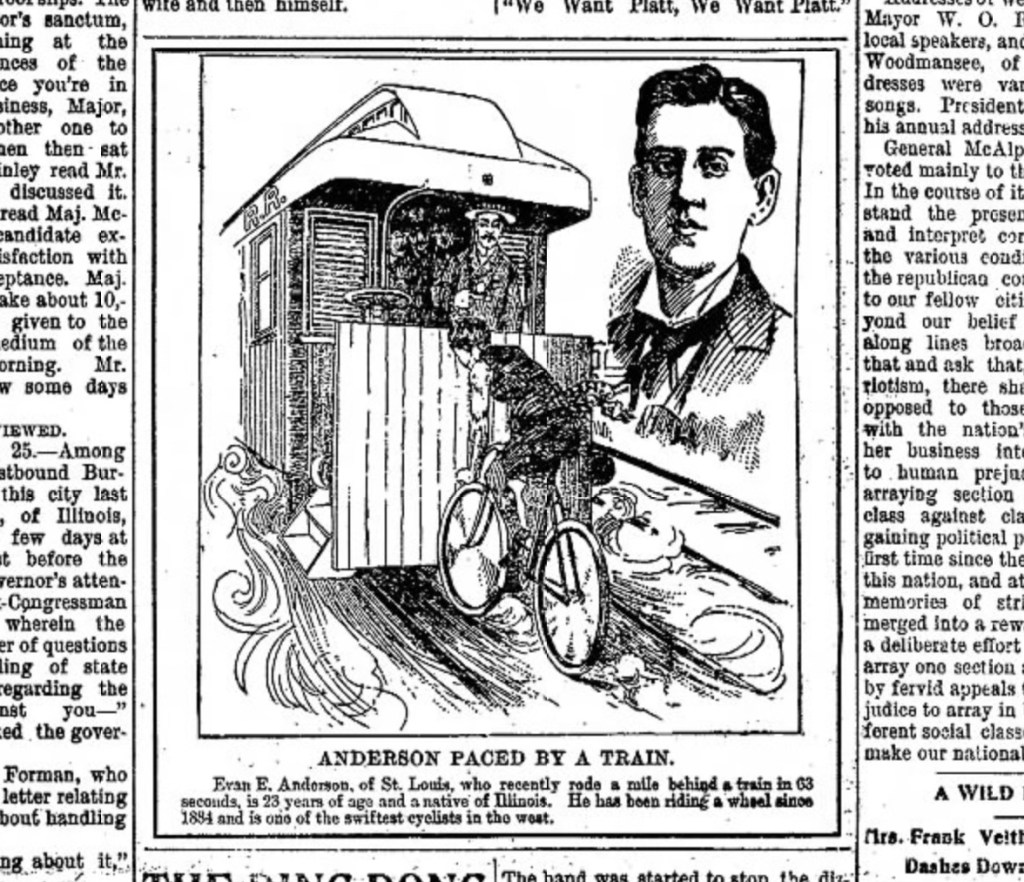

Pedaling behind a locomotive on tracks in Oldenburg, Illinois on August 9, 1896, professional cyclist E. E. Anderson covered a mile in 1 minute and 3 seconds. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported Anderson “was weakened by the ride … His tongue was skinned by the hot, sulphurous [sic] atmosphere and his lungs were ‘scorched.’ He also complained of a general feeling of ‘goneness.’”

Anderson proved it was possible and the race was on to be the first to ride a mile in a minute or less.

“Charles M. Murphy has not given up the idea of riding a mile a minute,” the Pittsburgh Daily Postreported on August 23, 1896. “As he cannot be paced by a locomotive in France [where he was racing at the time], he is on the lookout for a road with a steep incline. French cyclists are not enthusiastic over his idea, and say he stands more chance of breaking his neck than the record.”

Unable to find a railroad company willing to help or the perfect French hill to speed down (Mont Ventoux was not yet paved), Murphy made two attempts on the paved streets of Brooklyn. On November 4, 1897, paced by a sextet (a 6-person bicycle) he rode a mile in 1:50 on 22nd Avenue. He tried again on November 12, riding behind the sextet. The wind “was blowing as such a rate – almost 50 miles an hour … [and the riders] knew as they tore along the road with no obstacle to stop them that something was going to break, either a record or machine,” The New York World reported.

Murphy rode the mile in 1 minute and four-fifths of a second.

Doubts quickly sprung up about the authenticity of the announced time. The Sun reported Murphy was applying for official recognition, “but it is extremely doubtful if that organization will accept the claim for approval. Wheelmen are still smiling over the claim.”

Official recognition for the ride was never granted.

Over the next few years, there were several reports that Murphy, Anderson and other cyclists would make attempts at the mile-a-minute mark, paced by a locomotive. A race between Murphy and Anderson was planned near Chicago in May 1898. “The conditions of the match are that each man will be paced for a mile by the engine, and the one completing the distance in the best time will be awarded the money,” newspapers reported.

The match race never materialized. It’s easy to imagine Murphy growing more and more frustrated as the months and years went by. And then …

***

During the League of American Wheelmen’s state meet at Patchogue, Long Island in June 1899, Murphy “will attempt to ride a mile in one minute behind a Long Island Railroad engine and car,” The Standard Union of Brooklyn reported on May 29, 1899.

Finally, Murphy would have his chance at history.

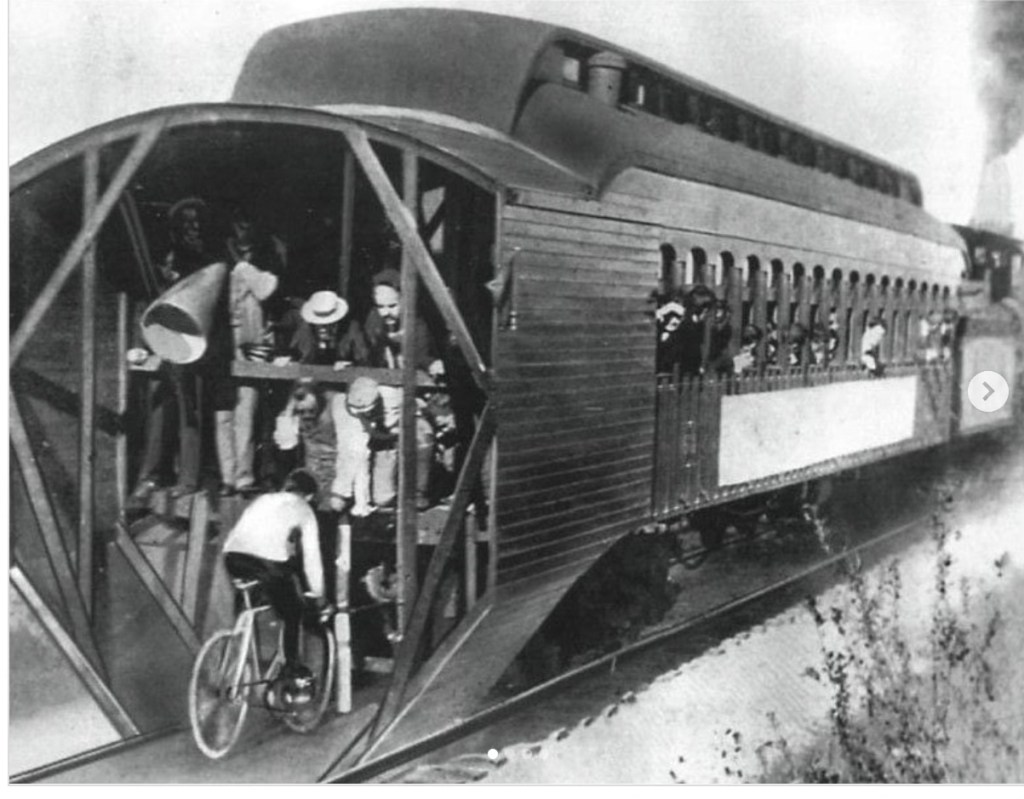

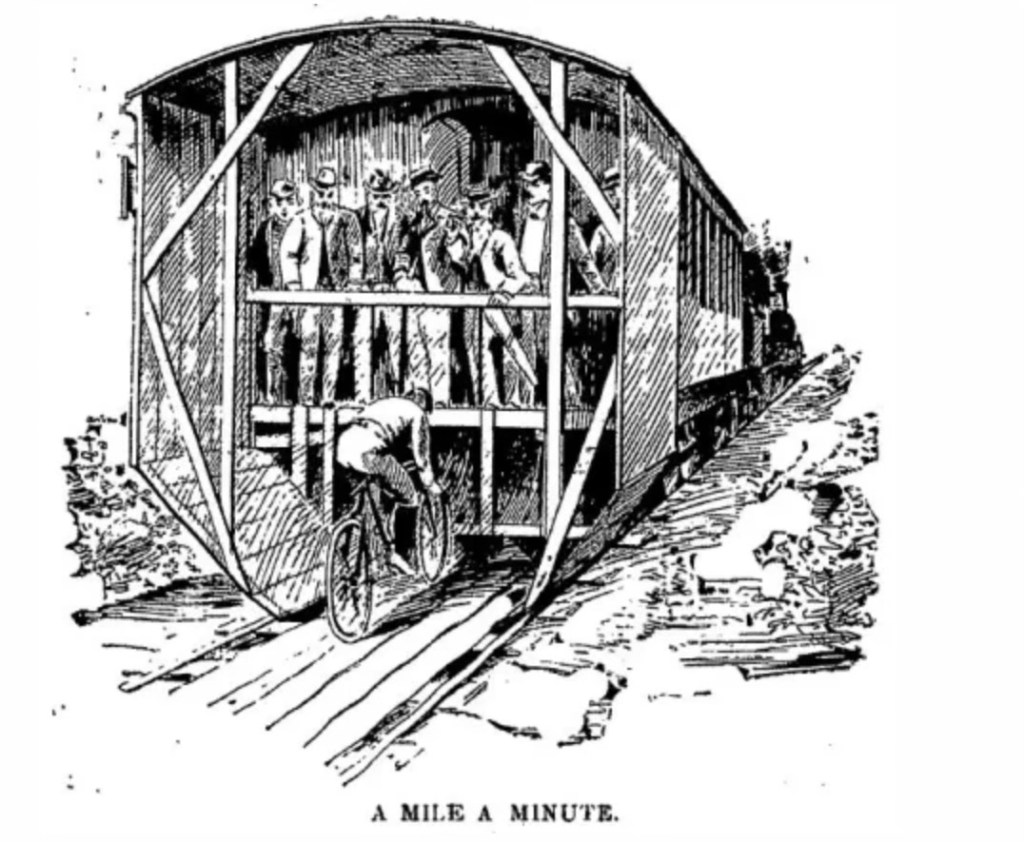

A trial run was set for June 21. Boards “planed to marble-like smoothness” were laid on a flat, straight stretch of track between the Maywood and Babylon stations. Murphy rode behind a wind screen that extended out from the back of the railroad car. “The train flew along, and with it flew the cyclist, his hair streaming and his body bent low, his front wheel not more than a foot away from the fender fastened to the car as a precaution against a mishap,” reported The Standard Union.

Murphy completed the mile in 1 minute and 5 seconds. He would later write that “this locomotive could not reach the mile-a-minute mark.”

A faster, more powerful train would be used on June 30 for the second and final run, Murphy’s best, and perhaps final chance at glory.

***

More than 1,000 people lined the 2.5 mile stretch of tracks. Murphy’s wife, a “young woman with a strong and pleasant face,” according to The New York Times, and their two young children were at the start. Murphy, wearing blue, woolen tights on his legs and a thin, light-blue jersey with long sleeves, spotted his family and waved as he prepared to ride.

About 50 men gathered in the car, including H. B. Fullerton, special agent of the Long Island Railroad, and the man responsible for organizing the event. At 5:10 p.m. the train began rolling, quickly picking up speed. Murphy held onto the rubber buffer (fender) extending from the rear of the car and wind screen. “He held on until he had kicked his pedals ten or twelve times, then he let go, stuck his head down, fastened his eyes on the strip of pine plank before him, and began to work,” The New York Times described.

Fullerton waved a white flag to indicate the start of the one-mile, measured and timed stretch of track. Murphy peddled furiously to stay as close as possible to the back of the car and take advantage of the “dead air.”

He covered the first half mile in 29 and two-fifths seconds. At this point he seemed “to be laboring and in trouble,” the Chicago Tribune noted. “He [dropped] back gradually, inch by inch, until he was entirely clear of the protection of the wind shield.”

Murphy would later say, “I offered up a prayer to God.” His prayer was answered and “an indescribable feeling came upon me. It was the hand of God. New vigor and energy came with every push of the pedals; the old bicycle responded like it never had before.”

He crept closer and closer to the back of the car and the full advantage of the dead air. His time after three quarters of a mile was 44 seconds. Murphy was on pace – and he and the train were picking up speed. “The roar and din of the of the train were terrifying to those watching Murphy,” wrote the Chicago Tribune. “The cyclist had lost his steadiness and was laboring madly. The whirlwind of dust, which followed him even inside the shield, beat about his head, blinded him, and probably was the cause of his unsteadiness.”

If Murphy have veered right or left, and off the planks, he could have easily been killed. He stayed on track and covered the final quarter mile in a blazing-fast 13 and four-fifths seconds.

His time for the mile was 57 and fourth-fifths seconds. He was now and forever Mile-A-Minute Murphy.

There was no time to celebrate. The end of the wooden planks was fast approaching and there was no way Murphy could stop before he hit the bare railroad tracks – and would most certainly crash. “A frantic yell of despair went up from the officials on the rear platform,” Murphy said. “They expected me to be dashed to pieces and sure death.”

Instead, Fullerton and another official reached out and grabbed Murphy. “As gently as possible Murphy, who had collapsed, was dragged over the rail,” the Chicago Tribune reported. “He sank unconscious but safe on the platform.”

***

The front pages of newspapers from coast to coast carried the news of Mile-A-Minute Murphy and his amazing feat. The Chicago Tribune called it the “most remarkable ride ever taken by a human being.” The Boston Globe wrote Murphy “made his fortune today in all probability, as the entire country will want to see the man now who rode the mile in less than a minute.”

Murphy did his best to cash in. The next day he rode a half-mile exhibition in Brooklyn, receiving enthusiastic applause from the crowd. And an appearance fee. He rode another exhibition in Hartford, Connecticut on July 7, covering a mile in 2 minutes and 2 seconds. A week later, Murphy raced – and beat – a horse in contest held in Torrington, Connecticut. “His services are greatly in demand,” wrote the Democrat and Chronicle of Rochester, New York.

Not everyone believed in the growing legend of Mile-A-Minute Murphy. Across the pond, The Guardian, in London, wrote the achievement “must be taken with the proverbial grain of salt.”

***

Murphy was past his peak as a racer by 1899, as the great Major Taylor had taken over as the fastest man on the circuit. Murphy performed a series of paid exhibitions on bicycles at races, on home trainers at cycling shows and even in vaudeville shows in theaters. At the January 1900 bicycle and automobile show at Madison Square Garden, 15,000 people watched Murphy ride a mile in 55 seconds on a home trainer.

In June 1900, Murphy announced his retirement from racing. The Buffalo Commercial reported he had won “any number of badges and trophies and now holds seven world records and seventeen state titles.”

A life of ease didn’t suit Murphy.

In early 1901, newspapers announced “Cyclist Murphy An Inventor.” His invention was a flying machine, and “as soon as the machine is completed he will give it a test.” It was never completed.Murphy announced in April 1901 he would ride his bike behind a specially designed, powerful automobile and “expects to cover the mile in :50.” There’s no record of an actual attempt.

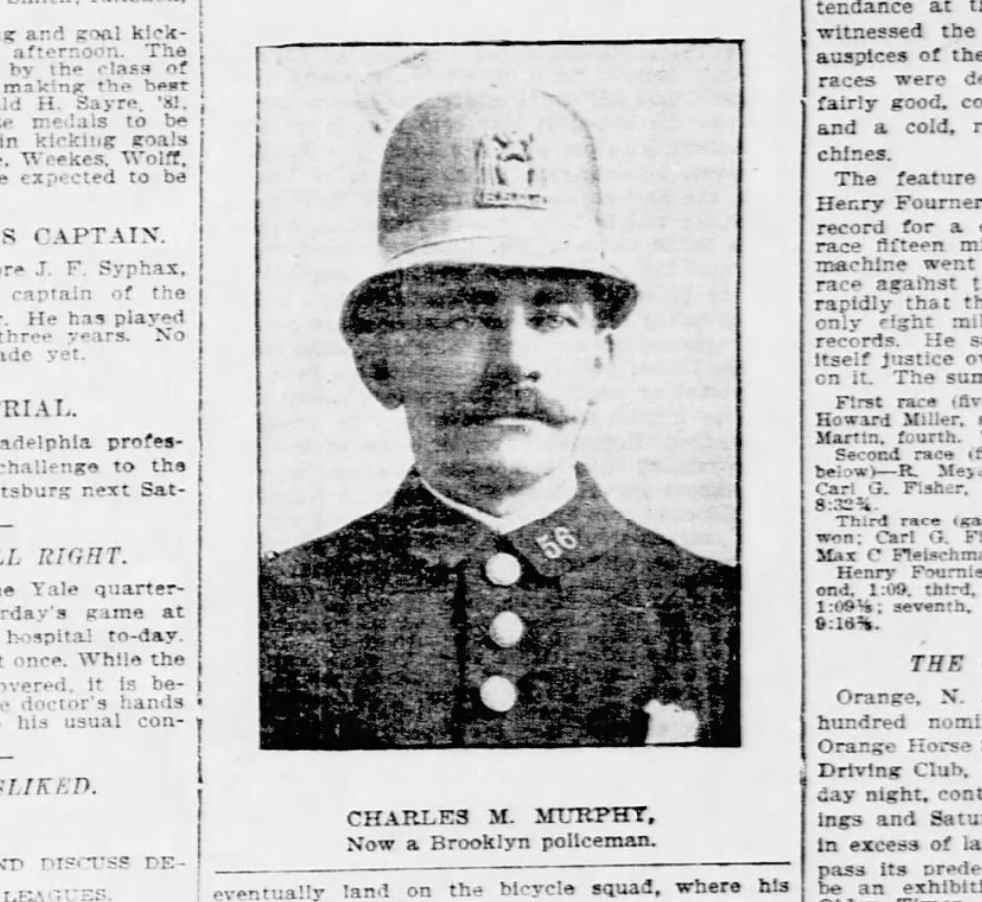

Seeking adventure and a perhaps a steady paycheck, Murphy joined the New York City Police Department in June 1901. He was assigned to a Brooklyn station as a bicycle cop, and later became the department’s first motorcycle cop. After a fire broke out on Fulton Street, Murphy “carried a hefty woman down a ladder from the third floor,” reported The Evening World. A few years later, a riderless “runaway truck horse” was racing down the street, threatening to trample a group of schoolchildren. “He is sheer grit, and by locking arms in a tight embrace around the animal’s neck, stopped its wind so that it staggered and finally came to a stop,” reported The Standard Union.

Murphy took flying lessons in 1913, hoping to become the department’s first airplane pilot, but couldn’t convince his superiors to create an air squad. After a series of on-the-job injuries, Murphy retired from the police department in 1917. “Murphy is physically disabled and may never again fully recover the use of his left leg,” reported The Standard Union.

He died on February 17, 1950, in Queens General Hospital. Mile-A-Minute Murphy was 79.